In which way does the canon of dance manifest itself in practice, and which types of canonized bodies are being taught in the context of dance education? Anna Chwialkowska relates her experiences with somatic practices within her dance education, and the boundaries she encountered.

Text: Anna Chwialkowska

Anthropologist, Dramaturg and Dancer

What is the dance canon? Does the dance canon move? If so, how? What’s its movement quality? Is it dense? Multi-directional? Does it shake or float? Contract and release? What does it know about partnering? Can it move like an octopus with all its limbs independent from each other? Does it use its peripheric gaze? And aren’t those questions already part of a canon that were instilled in me?

For more than a year, I have embarked upon an autoethnographic journey researching (mostly informal) contemporary dance training settings. I started examining what contemporary dance practices teach, transmit, include and leave out, or in short: what they pretend to be currently in such a heterogenous and both privileged and precarious dance location as Berlin.

These are weird times to be a dance student. Before I knew the canon, I got to know the anti-canon. During a 10-month intensive contemporary dance training, my poor attempts at learning any technique (like ballet or whatever else is considered as the classic dominant dance) have always led to a dead end. It just wasn’t part of the curriculum. Admittedly, I have also been a bit lazy to take extra ballet classes apart from the obligatory schedule. But no one would really push or motivate me to learn it, either.

During the program, I heard teachers say more than once that what professional dancers do is so unhealthy for their bodies and that our priority would be to take care of ours. What followed were sequences of minimal movement and somatic endurance practices. Sometimes, I felt there was something wrong about it , but couldn’t put it into words. This year, it came to me in two epiphanies.

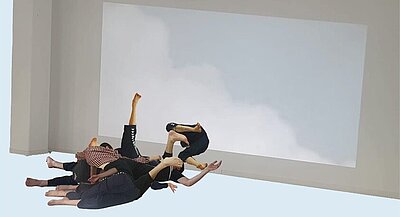

Epiphany 1: Observing a choreographer that typically trains and works with professional dancers hold a workshop for a bunch of exhausted undergraduate dance students. As a warmup, he proposed a standing movement meditation, consisting of a thorough body scan that implies focus on one’s interior, on the most minimal of movements. Professionals are grateful for those kinds of practices that lack any requirement of virtuosity. The students, however, could barely take it. Some of them sat down or were lying on the floor after the first couple of minutes. Some started engaging in outward-reaching movements despite the fact that movement had not been suggested. As the choreographer was about to start the same practice the next day, a student bluntly asked, “Do you have another proposition that doesn’t feel like a prison?” Funnily enough, somatic practices are supposed to do the exact opposite: namely, freeing the dancing body from the constraints imposed on it by techniques. While being an important complementary training for professional dancers, it seems difficult to find that kind of “freedom” in Somatics for someone who has only just stepped foot in the studio.

Epiphany 2: Reading about the universalizing concepts of what a natural body is in somatics dance training (Doran George 2020), I understood that the majority of my training drew on exactly these kinds of principles – directly or indirectly. Therefore, I propose that Somatic practices themselves, portraying supposedly “healthy” and “natural” forms of movement, often based on scientific knowledge, can also be viewed a canon. George’s book made me dizzy with all the information on how early twentieth century Somatics practitioners such as F. M. Alexander conceptualized their practices. You can find anything from evolutionary theory to ideas on “primitive minds”, and alongside examples like children and animals, “tribal non-Western people” are drawn upon as a kind of idealization of a “precultural” movement. A lot of these early ideas endured washing away the “memory of racist and eugenic rhetoric in early twentieth-century Somatics as if it were irrelevant to more enduring insights” (George 2020).

Don’t get me wrong, Somatics helped me a great deal in enabling me to talk about and understand my body in many ways beyond dance training. I do wonder, though, why dance students never get that history class.

Bibliography:

George, Doran (2020) The Natural Body in Somatics Dance Training. Oxford: Oxford University Press.